This post is an adapted excerpt from Understanding the Odin Programming Language – the acclaimed eBook on learning Odin and understanding low-level concepts. Visit https://odinbook.com for more information.

Text strings in Odin use Unicode. Unicode is a standard that makes it possible to use characters from most languages. You can mix different languages within the same string, and even use exotic things such as emojis!

Odin has two primary types for representing text: string and cstring. You’ll mainly use the string type in your Odin code. The cstring type is for working with libraries written in the C programming language. Both types use the UTF-8 encoding, short for Unicode Transformation Format - 8 bit. UTF-8 is the most popular way of storing Unicode text in memory.

There are two more string types called

string16andcstring16. Those use the UTF-16 encoding. They are only used in some specific cases (such as with the Windows API). They are covered in the full eBook.

This post is about understanding the interplay between UTF-8 and Unicode. We’ll talk about runes (Unicode code points) and how iterating a UTF-8 string automatically decodes it into runes. Thereafter we’ll look at how to manually decode a UTF-8 string by inspecting its memory.

Iterating strings

In the following example we iterate a UTF-8 string. For each lap of the loop, the loop variable r will contain a character from the string.

str: string = "Important Words"

for r in str {

// r is of type `rune`

}

The loop variable r is of type rune. A rune is just a 32 bit (4 byte) number. In many cases (but not all!), a rune represents a single character. For example the letter K is represented by a rune of value 75. The name “rune” is specific to Odin. Outside of Odin, a rune is called a Unicode code point.

The numeric values of code points are decided by the organization known as the Unicode consortium. They try to make a wide variety of characters, from many languages, possible to express using code points. For example, they’ve decided that the letter

Qhas the code point value81and that the Chinese character猫has the code point value29483.

When we talk about grapheme clusters (full eBook only) you’ll understand why I wrote “In many cases (but not all!), a rune represents a single character”.

When our program stores a string in memory, such as in the variable str, then it doesn’t store it as a series of 4 byte rune values. Instead, it stores each rune using 1 to 4 bytes. That’s the UTF-8 encoding. As the loop in our example runs through the UTF-8-encoded string, it decodes sequences of 1-4 bytes into runes.

You can see it as a type of compression: A rune is a 4 byte integer. But in many cases you can store such a number using fewer bytes. For example, the letter W has the code point value 119. UTF-8 encodes that using just a single byte, saving you three whole bytes of memory!

In UTF-8 encoded strings, all English characters need just a single byte. But characters from other languages may use more than a single byte. In the following example we iterate a string written in Simplified Chinese:

str := "小猫咪"

for r in str {

fmt.println(r)

}

Which will print:

小

猫

咪

Within the memory of the UTF-8 string str, these Chinese characters use 3 bytes each. As the loop runs through the string, it decodes those groups of 3 bytes into proper 4 byte runes.

The UTF-8 decoder knows if it is processing a 1, 2, 3 or 4 byte rune. A few bits in each byte is dedicated to signaling if the rune continues, or if it is complete. In the next section, I’ll show how to manually decode UTF-8 by inspecting the value of each byte.

A note for Windows users: You may see garbage in the command prompt when printing the Chinese characters. In that case, try running

chcp 65001in the command prompt, before executing the program. Alternatively, addwindows.SetConsoleOutputCP(.UTF8)at the top of themainproc (import "core:sys/windows). This works fine on Windows 11. If you are on Windows 10, then you might need a better command prompt program thancmd. I recommend ConEmu, which wrapscmdwith some nice features. I don’t recommend PowerShell, it is buggy.

It’s important to understand that a rune, or Unicode code point, is independent of how the string is encoded. There are several different encodings, such as UTF-8 and UTF-16. Those encodings just decide how the string is stored in memory and how to turn that memory back into runes. The decoded value of the rune is the same, regardless of encoding.

Manually decoding UTF-8

Let’s take a look at what the memory of a UTF-8 string looks like and how you can manually decode it into runes. A loop such as as for r in str {} does this decoding for us. This section will help us understand what work that loop actually does.

Here is some code that iterates a string and prints each rune on a separate line:

str := "Cät=猫"

for r in str {

// Prints the characters of `str` on separate lines.

fmt.println(r)

}

We want to investigate the bytes of the UTF-8 encoded string, without decoding them into runes. Therefore, we transmute the string to a slice of u8 (byte). We can then loop through the bytes and print them in binary:

str := "Cät=猫"

str_bytes := transmute([]u8)(str)

for b in str_bytes {

fmt.printfln("%8b (%v)", b, b)

}

transmute([]u8)(str)takes the memory of the string and “pretends” it to be of type[]u8. A slice of bytes and a string are more or less the same thing. But no automatic UTF-8 decoding will happen when we loop through the[]u8version. This makes it possible for us to inspect the encoded bytes. The%8bformat string tellsprintflnto print the number in binary. The8in%8btells it to add zero padding on the left, so we always see 8 binary bits.

The output is:

01000011 (67)

11000011 (195)

10100100 (164)

01110100 (116)

00111101 (61)

11100111 (231)

10001100 (140)

10101011 (171)

Let’s manually go through the bytes, construct Unicode runes from them and print each one to verify that we did it correctly.

Rune C (byte 01000011)

01000011: The first bit (the left-most bit) is zero. This means that this is a single-byte rune. The byte just needs to be cast into a rune in order to complete the decoding:

fmt.println(rune(0b01000011)) prints C.

The

0bprefix tells the compiler that we have provided a binary value.

Note that a rune is just a 32 bit number. But we cast to rune instead of i32. This is so fmt.println shows it as a character instead of a number. But memory-wise, i32 and rune are identical.

Rune ä (bytes 11000011 and 10100100)

11000011: Start with 110. This means that this is the beginning of a multi-byte rune. The number of bytes to expect for this rune is two, because there are two 1s. We throw away the initial 110 and remember the rest: 00011. Then we move to the next byte.

10100100: Starts with 10. This means that this is a continuation of a multi-byte rune. The previous byte told us to expect two bytes (including the initial one), so this is the last byte. We throw away the 10 and combine the remainder with the result from the previous byte: 00011 and 100100. Simply copy-paste them together: 00011100100. Try printing it:

fmt.println(rune(0b00011100100)) prints ä.

As you see, the main work in decoding UTF-8 is the following: Check if the byte starts with a 1. If it does, then you count how many 1s there are until the first 0. Then use that information to classify the byte.

Rune t (byte 01110100)

01110100: The first bit is zero, this is a single-byte rune. Just cast into rune and print:

fmt.println(rune(0b01110100)) prints t

Here you also see why UTF-8 is backwards compatible with the first 128 values of ASCII. ASCII uses a single byte for each character. UTF-8 can also represent some characters using a single byte, if the first bit is zero. But then there are only 7 out of 8 bits left. 7 bits gives us a numeric range of

0-127, or 128 values. Those 128 values have been chosen to represent the same characters as in ASCII.

Rune = (byte 00111101)

00111101: The first bit zero. Just cast into rune and print:

fmt.println(rune(0b00111101)) prints =

Rune 猫 (bytes 11100111, 10001100 and 10101011)

11100111: Starts with 1110: Three 1s mean that this is the start of a triple-byte rune. Throw away 1110 and remember the rest: 0111.

10001100: Starts with 10: This is a continued multi-byte rune. Throw away the 10 and remember the rest: 001100

UTF-8 is said to be “self-synchronizing”: Imagine looking at a random byte in a UTF-8 string and noticing that it start with the bits

10. Those starting bits are only used for “continuation bytes”. You can always find where the rune starts by stepping backwards in the string, byte-by-byte, looking for the first byte that doesn’t start with10.

10101011: Starts with 10: Continued multi-byte rune. Throw away the 10 and remember the rest: 101011. This is the last byte in the three-byte sequence. Copy-paste the bits together: 0111, 001100, 101011 -> 0111001100101011. Cast to rune and print:

fmt.println(rune(0b0111001100101011)) prints 猫.

And we are done!

We didn’t see any four-byte runes. But it’s the same dance: The first byte starts with 11110 (four 1s). Then follows three bytes starting with 10.

As an exercise, try adding an emoji to the string and manually decode it. Many emojis are encoded using four bytes. However, some emojis may use multiple runes (they are grapheme clusters, which I cover in the full eBook).

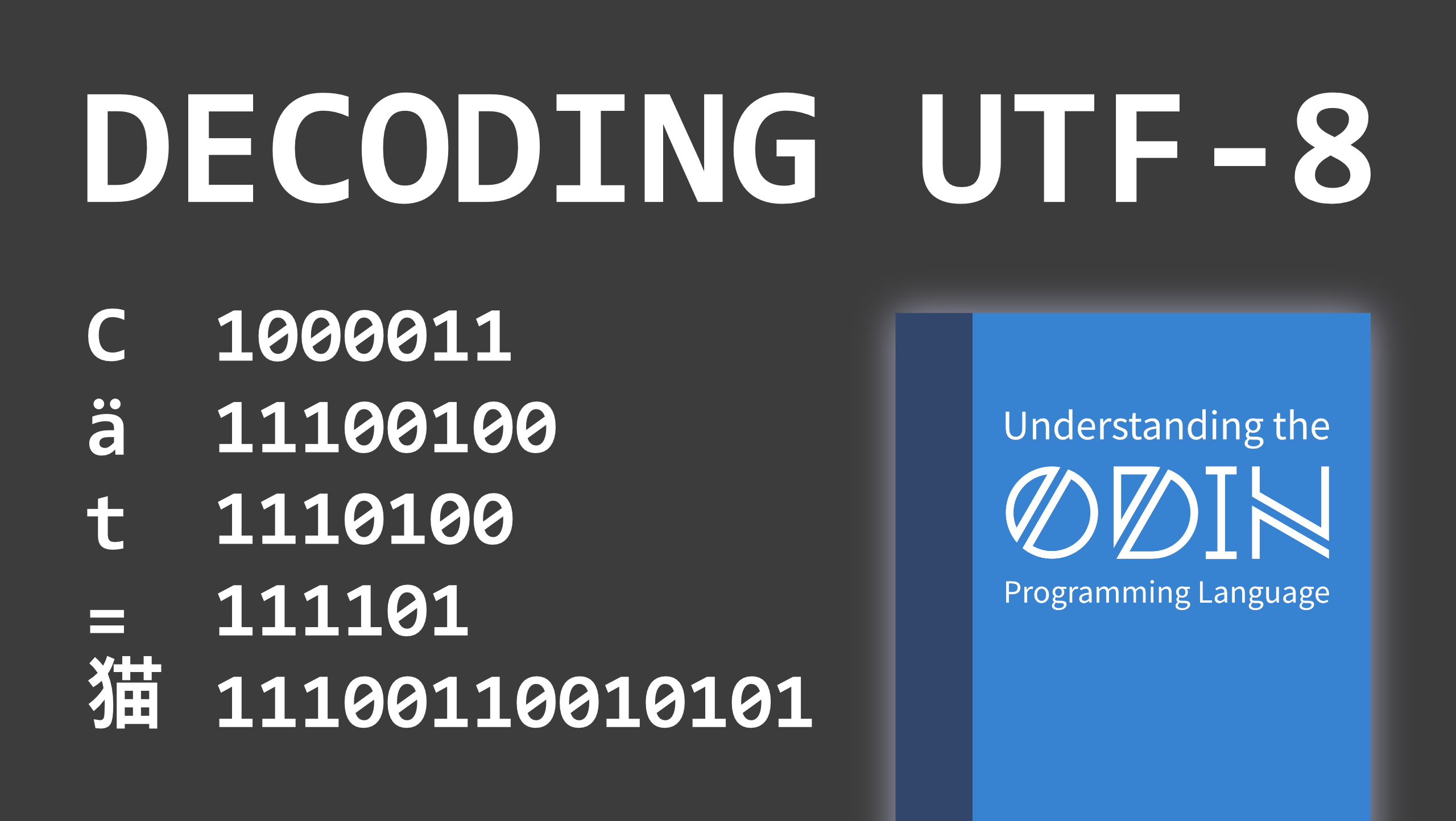

You can verify our results by looping through the string as usual (loop through str, not str_bytes) and printing the automatically decoded runes as binary numbers:

str := "Cät=猫"

for r in str {

fmt.printfln("%b", r)

}

It will print the same binary numbers that we found:

1000011 (C)

11100100 (ä)

1110100 (t)

111101 (=)

111001100101011 (猫)

Any padding of zeroes on the left is not present here. Zero padding on the left of a binary number can often be thrown away, unless you want to keep the zeroes to hint at a specific bit width.

A real UTF-8 decoder would do some additional error checks while decoding. But the knowledge in this section is sufficient to investigate the memory of most UTF-8 strings.

There’s a procedure in core:unicode/utf8 called decode_rune. Check that one out for an actual implementation of what we have discussed in this chapter.

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed the contents and style of this blog post, then check out Understanding the Odin Programming Language. It is an eBook entirely written in this casual, friendly style: https://odinbook.com.

The book is roughly 47 times the size of this blog post.

There’s also a video version of this blog post:

Have a nice day!

/Karl Zylinski