In my post “Handles are the better pointers”: An Odin gamedev follow-up I talked about how one can implement a handle-based map in Odin.

In this post I want to follow that up by talking about three specific variants of a handle-based map, and highlight what sets them apart.

The three variants are available in this repository: https://github.com/karl-zylinski/odin-handle-map

NOTE: In the old post I used the term “handle-based array”, I’ve since then switched to saying “handle-based map”. It’s more of a map than an array, really.

Quick recap: What’s a handle-based map?

A handle-based map is a storage container that maps a handle (index + generation) to an item.

The handle can be used as a permanent reference to the items in the map. In other words, the handle can be used where you would normally store a pointer or index.

Handles are good because they store the index (“which item?”) and also the generation (“is it actually still the same item?”). Compared to using pointers, using handles also reduces the risk of crashing due to usage of dangling pointers to items.

A common use case for handles is when you need to store references to entities in video games, which we’ll see some examples of below and in the examples folder of the repository.

Let’s look at the three variants and follow it up with some additional discussion.

Variant 1: handle_map_static (source)

The simplest way to make a handle-based map is by wrapping a fixed array with some book-keeping. That’s what the handle_map_static does. The Handle_Map struct inside it looks like this:

Handle_Map :: struct($T: typeid, $HT: typeid, $N: int) {

// Each item must have a field `handle` of type `HT`.

//

// There's always a "dummy element" at index 0. This way, a Handle with

// `idx == 0` means "no Handle". This means that you actually have `N - 1`

// items available.

items: [N]T,

// How much of `items` that is in use.

num_items: u32,

// The index of the first unused element in `items`. At this index in

// `unused_items` you'll find the next-next unused index. Used by `add` and

// originally set by `remove`.

next_unused: u32,

// An element in this array that is non-zero means the thing at that index

// in `items` is unused. The non-zero number is the index of the next unused

// item. This forms a linked series of indices. The series starts with

// `next_unused`.

unused_items: [N]u32,

// Only used for making it possible to quickly calculate the number of valid

// elements.

num_unused: u32,

}

Here the items array is of type [N]T. That’s a fixed array of size N, where N is passed as a polymorphic parameter when declaring the struct.

You declare a static handle-based map like so:

// import hm "handle_map_static"

Entity_Handle :: distinct hm.Handle

Entity :: struct {

handle: Entity_Handle,

pos: [2]f32,

}

Entity_Handle :: distinct hm.Handle

entities: hm.Handle_Map(Entity, Entity_Handle, 1024)

h := hm.add(&entities, Entity { pos = { 5, 7 } })

if e := hm.get(&entities, h); e != nil {

e.pos.y = 123

}

As you can see we feed 1024 into N here. Since it uses a fixed array (sometimes known as a “static array”), the Handle_Map will always use 1024*size_of(Entity) bytes of memory. The memory usage will never shrink or grow, and you must specify how many things you want up-front.

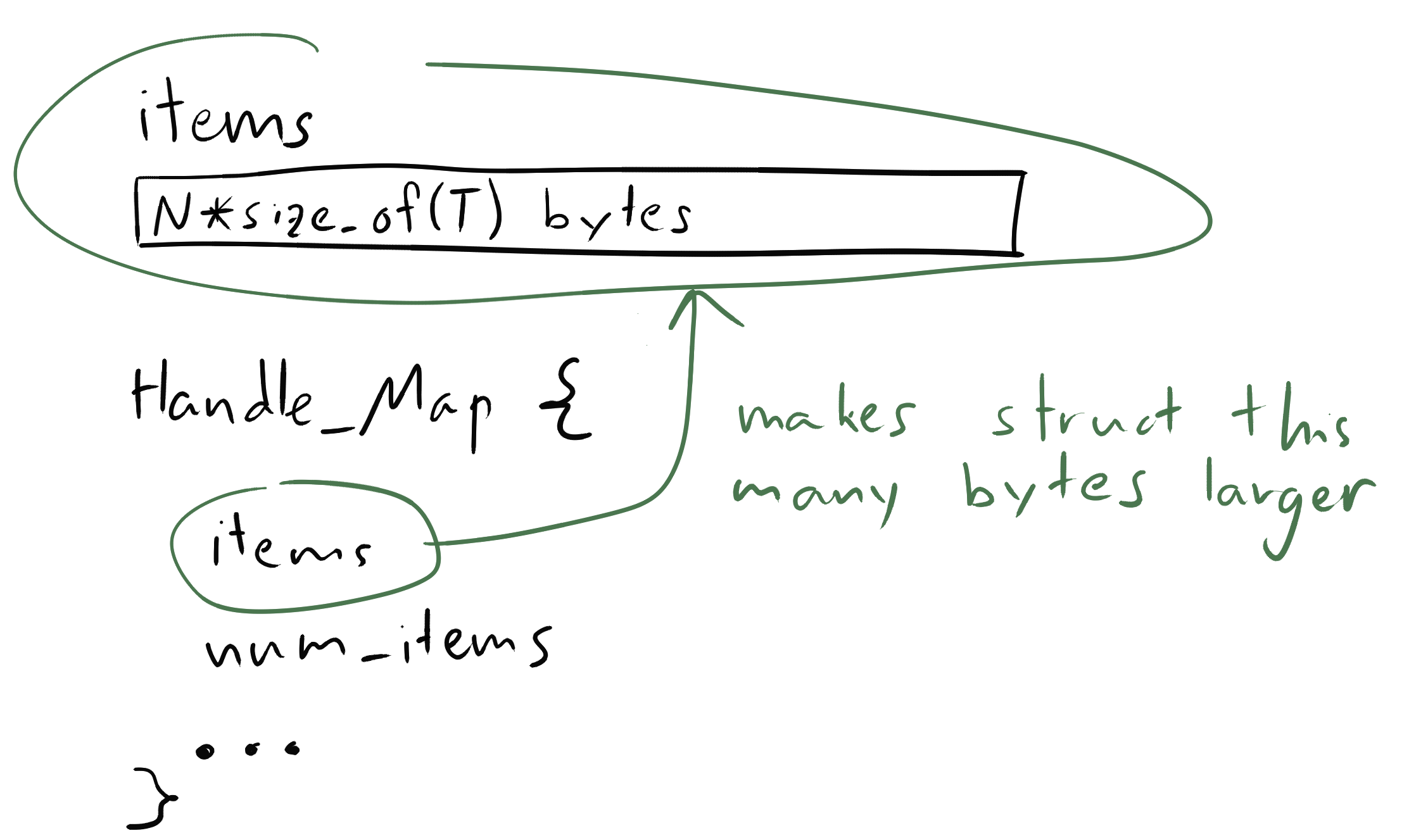

Handle_Map uses N*size_of(T) directly within the struct, due to the fixed array living ‘inline’ in the struct.

Having to specify how many things you want up-front can both be a good and bad thing: You must think about the worse-case scenario! But in some cases it is hard to know how the user of the program will use it. Perhaps some users will have 10 items in the map, while other’s have 2 million.

Since fixed arrays are fairly simple, this variant supports web builds. See a live demo here: https://zylinski.se/odin-handle-map-fixed-example/

It’s fairly easy to make this variant work with SoA (Structure of Arrays). You’ll mostly need to change items: [N]T into items: #soa [N]T in the Handle_Map struct. See the comment about SoA in the performance_comparison program for more info.

You can learn more about SoA in the “Data-oriented design” chapter of my book Understanding the Odin Programming Language

Pros

- Simple

- No manual memory management

- Pointers are stable (I’ll return to this at the end of the post)

- Always uses as much memory as the “worst case scenario”

- Easy to convert to SoA format

- Works on web

Cons

- Always uses as much memory as the “worst-case scenario” (this is both a good and a bad thing!)

- Can’t grow

- Figuring out “worst-case scenario” size can be tricky in some cases

- You can easily blow up the stack since the

Handle_Mapstruct can get very large

Variant 2: handle_map_static_virtual (source)

Just like with Variant 1, you need to specify a “maximum size” when working with this one. The Handle_Map struct looks like so:

Handle_Map :: struct($T: typeid, $HT: typeid, $Max: int) {

// Each item much have a field `handle` of type `HT`.

//

// There's always a "dummy element" at index 0. This way, a Handle with

// `idx == 0` means "no Handle".

items: [dynamic]T,

// Arena that stores the data for each of the items. It will have room for

// `Max` number of elements.

items_arena: ^vmem.Arena,

// The indices of unused slots. `remove` will add things to it and `add`

// will remove things from it.

unused_items: [dynamic]u32,

}

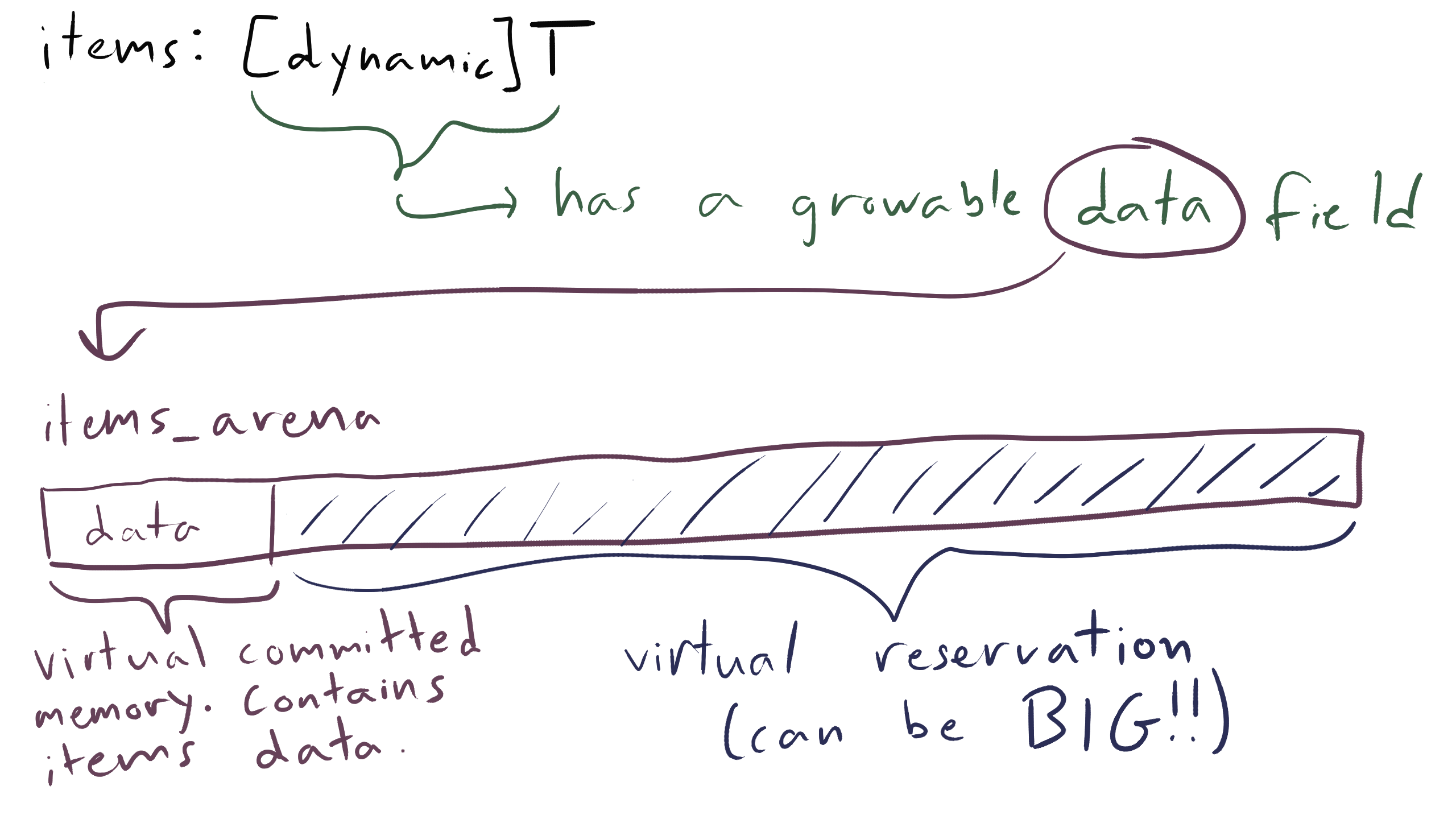

First thing to notice is that this uses items: [dynamic]T. In Variant 1 we just had items: [N]T.

There’s also a virtual memory arena: items_arena: ^vmem.Arena. When the handle-based map is created, the dynamic array items is set up to use that arena. The elements of items all live in there.

vmemis an alias of the packagecore:mem/virtual

The setup of this kind of Arena is similar to variant 1:

// import hm "handle_map_static_virtual"

Entity_Handle :: distinct hm.Handle

Entity :: struct {

handle: Entity_Handle,

pos: [2]f32,

}

Entity_Handle :: distinct hm.Handle

entities: hm.Handle_Map(Entity, Entity_Handle, 1000000)

h := hm.add(&entities, Entity { pos = { 5, 7 } })

if e := hm.get(entities, h); e != nil {

e.pos.y = 123

}

Note that we can use a very big “max number of items” number: Here it is 1000000. The virtual arena will reserve virtual memory for that many elements. But that’s just a reservation. It does not result in consuming that amount of memory. Only as the dynamic array grows into that reserved space does the memory usage increase.

items has a field inside it called data (see Raw_Dynamic_Array). That’s a growable block of data that contains the dynamic array’s data. By allocating this data into a big static virtual arena, it can grow without moving in memory. That’s good for keeping pointers stable. Note that the dynamic array can grow, but the amount of memory reserved in the arena can never grow. The dynamic array grows into that arena’s memory.

See the

makeproc inside the source for how the arena is created and set up.

A benefit compared to Variant 1 appears: We can start with low memory consumption and have it go up as we go. This would happen if you use items: [dynamic]T without any arena as well. However, because of how we use the virtual arena, the data of the dynamic array will not move when the dynamic arrays grows. This makes pointers to items in the arena stable. You should still store handles when storing permanent references to the items. But whenever you need to temporarily access the item you’ll resolve the handle into a pointer, like we do with e:= hm.get(blabla) above.

The dynamic array not having its data moved when it grows works because the virtual arena can re-allocate the dynamic array’s data if no other allocation has happened since the dynamic array allocated that memory.

You can read more about how combining areans and dynamic arrays can be both good and bad in my post on Arenas + Dynamic Arrays.

Pros

- You can start with small memory usage (more memory efficient than variant 1)

- Not very complicated

- Pointers are stable

Cons

- You can’t use it on web (WASM does not support virtual memory. On web use Variant 1 or 3).

- You must specify an upper estimate of the size, although it can be exaggerated

Variant 3: handle_map_growing (source)

This variant does not require you to specify any kind of upper estimate for the size. It works on web. But it is more complicated.

The Handle_Map struct of it looks like this:

Handle_Map :: struct($T: typeid, $HT: typeid) {

// Each item in this array is allocated using `items_arena`. This array is

// allocated using `context.allocator`, not using the arena. Only the items

// themselves are allocated using `items_arena`.

//

// Each item much have a field `handle` of type `HT`.

//

// There's always a "dummy element" at index 0. This way, a Handle with

// `idx == 0` means "no Handle".

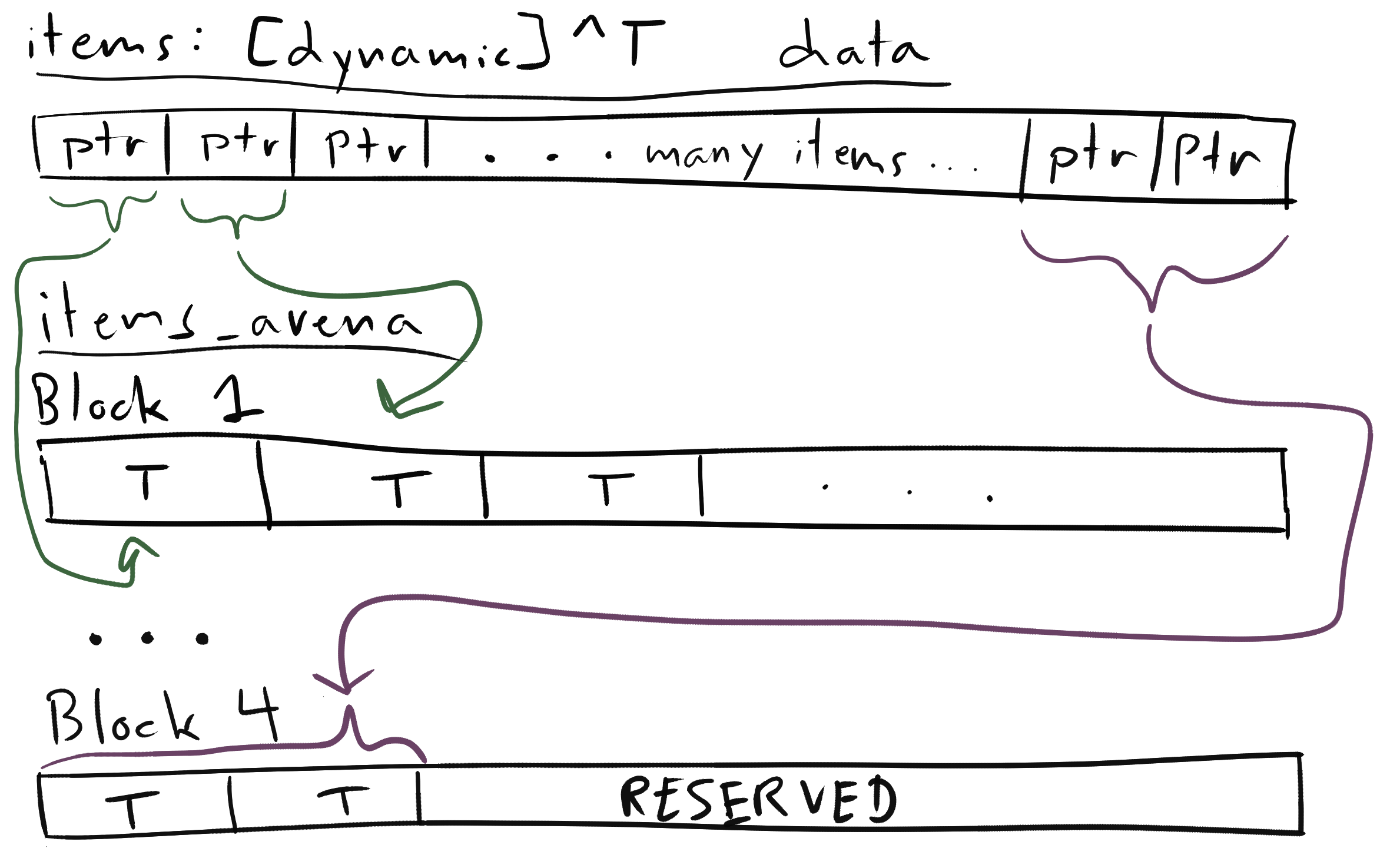

items: [dynamic]^T,

// Arena that stores the data for each of the items. Since all of them are

// allocated linearly into this arena, it means they are fairly well packed.

// This gives stable pointers combined with good performance.

//

// Uses a Growing Virtual Arena on non-web platforms. On web platforms a

// Dynamic Arena is used. See `arena_default.odin` and `arena_js.odin`

items_arena: Arena,

// The index into `items` of unused slots. `remove` will add things to it.

unused_items: [dynamic]u32,

}

Note that it says just

Arena. On non-webArenaisvmem.Arena. On web it ismem.Dynamic_Arena(fromcore:mem). This abstraction is done using the twoarena_xx.odinfiles in the same folder.

One thing that may jump out is this: items: [dynamic]^T. In the other variants I stored elements of just type T. Why the need for the pointer? It has to to with how I allocate the items.

^T. So each item is just a pointer that refers to something else. Those pointers refers to the items of type T that are allocated in the arena. The arena consists of blocks of virtual memory. The blocks are by default 1 megabyte. That’s big, but OK since it’s just a virtual reservation: The memory usage only goes up as new items are allocated, which will make the arena commit more and more of that reservation. Here ‘commit’ means ‘map reserved virtual memory to actual physical memory’

With this variant I use a virtual growing arena. That arena consists of blocks of memory. When the current block is full, it virtually reserves a new one. It’s not the items dynamic array that uses it. Rather, I dynamically allocate each item into it. In other words, the allocation of each item looks something like this:

items_allocator := arena_allocator(&m.items_arena)

new_item := new(T, items_allocator)

new_item^ = v // v is the item to be added to the handle-based map

new_item.handle.idx = u32(builtin.len(m.items))

new_item.handle.gen = 1

append(&m.items, new_item)

This code is from the

addproc in the source.

As I described in my post on arenas and dynamic arrays, the items you allocate like this will end up one-next-to-each-other, since the arena just grows linearly. So the items are still fairly well-packed, which is good for making the code cache-friendly.

This means that the array items just contains a bunch of pointers into the arena’s memory.

WARNING:

itemsis not, and should not be allocated into the arena. It will use the default allocator (or some other allocator you feed intohm.make). If you put it into the arena then it would waste memory due to leaving its old data behind in there. It would not be able to reuse the old data blocks due to the calls tonewin the addaddproc also allocating into the arena. Those allocations will end up in-between the array’s old and new data blocks, so it would not be able to reuse the same address. This is not as bad as in Variant 2 since the address of each item would still be stable, but you’d waste memory by leaving old dynamic array data in the arena. Again, see my arenas and dynamic arrays post for more info.

I’ve tried to make this variant universally usable. It does work on web, but WASM does not support virtual memory. In that case it uses a Dynamic_Arena instead. That arena also uses blocks and the items of the array will be allocated into those blocks. But unlike the virtual arenas, the blocks always use the “full amount of memory” directly.

The

Dynamic_Arenahas a default block size of65536bytes. So the program’s memory usage will increase in steps of that amount. It may be wise to tweak the the block size to a larger number if you store very big items in the array, as each block would otherwise become full very quickly.

Declaring a handle-based map of this type is done like so:

// import hm "handle_map_growing"

Entity_Handle :: distinct hm.Handle

Entity :: struct {

handle: Entity_Handle,

pos: [2]f32,

}

entities: hm.Handle_Map(Entity, Entity_Handle)

h := hm.add(&entities, Entity { pos = { 5, 7 } })

if e := hm.get(entities, h); e != nil {

e.pos.y = 123

}

As promised, no magical number that represents a “maximum size” needs to be fed into Handle_Map.

Pros

- Can start with small memory usage (better on non-web, but web is OK too due to block-based arena)

- Pointers are stable

- Works on desktop and web

- Simple to use, no need to specify maximum size

Cons

- Complicated implementation, harder to understand

- Pointer indirection for each item (but still fairly well packed in the arena, which is good for being cache friendly)

Which one should I use?

I’d probably go with Variant 2 and choose an exaggerated maximum size. However, that one does not work on web. So if you need web support perhaps you can use Variant 1 on web, or just use Variant 3 everywhere.

If you have a good feeling for how much memory you need, then you can use Variant 1 everywhere.

Perhaps there could be some value in creating a combined implementation that uses

Variant 2on non-web (big static virtual arena) andVariant 3on web (mem.Dynamic_Arenathat stores the items, with pointer indirection in the items array). But those implementations differ so much that you’d need to abstract away almost all the handle-based map code, not just the arena.

“Pointers are stable”

You may have noticed that I wrote “Pointers are stable” in the “Pros” list on all three variants. That’s because I want to talk a bit extra about that here.

The pointers I refer to are the ones you get when you do this:

e := hm.get(entities, some_handle)

Here get returns a pointer. Some implementations of handle-based maps use dynamic arrays straight up, without any kind of arena or fixed array. That will make pointers become invalid if the dynamic array grows while you have such a pointer in flight.

In other words, look at the code below. In it, I get a pointer e based on a handle. Then I add a new item to the handle-based map. Then I use whatever e points to.

e := hm.get(entities, some_handle)

hm.add(&entities, Entity{ pos = { 5,1 } })

if e != nil {

e.pos += {2, 1}

}

The code above will always work fine with the three variant’s I’ve presented in this post. If the handle-based map used a dynamic array without any of the arena tricks (or fixed arrays), then e might point at deallocated memory if hm.add caused the dynamic array to grow.

Now you may say: “This seems silly, isn’t the point of the handle-based map that you should try to keep things as handles for as long as possible, and only resolve to pointers at the last moment?”. I talk about this in my previous post on the topic. To summarize my thoughts on this:

- When you try to ship a product you’ll start adding polish.

- Polish might mean adding things to handle-based maps at convinient places in the code (such as an entity that represents a graphical effect in a game)

- Adding it will sometimes make your handle-based map grow

- It’s not unlikely that you are using pointers to an item from a handle-based map in the same procedure. If you don’t have stable pointers, you will now be sad.

Now you may say another thing: “That’s fine, but if the pointers are stable, what’s the point of the handles? You can just store pointers permanently!! All you need is a fixed array!”

Yes, you can. But your program may have several systems that all poke at the same array. This is common in games, hence my video game “entity” examples. Say that system A and B both store pointers to entity X. Then system A may destroy entity X and at its place put entity Y. But system B will not know that this has happened and may continue using entity Y, thinking that it still represents entity X.

With handles this does not happen. The generation counter on the handle makes sure that the handle references something that is still present in the handle-based map.

You don’t need to use handles instead of pointers for all your references. You can start with simple fixed arrays and pointers, you’ll quite quickly see which arrays that have this problem: It’s often the ones that are accessed by multiple systems, where systems can add and remove things from the array.

Using removed items

One thing that can still go slightly wrong is the following:

e := hm.get(entities, some_handle)

hm.remove(&entities, some_handle)

if e != nil {

e.pos += {2, 1}

}

Here we resolve handle some_handle to pointer e. Then we remove that entity from the list. But we already have the pointer around, so you may end up using it after the removal.

The code after

hm.getcould also have added removed it and then added new items, which may have recycled the slot. Thenewould point at something else than you expected.

I’d say that this is fine. It’s much less of a problem than unstable-pointers-when-the-array-grows. It may sometimes cause a slight logic error, but it won’t make your program crash.

Video

I’ve made a video that covers roughly the same stuff as this blog post:

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this article, then perhaps you’d enjoy my book “Understanding the Odin Programming Language”. It contains deep dives into manual memory management and how dynamic arrays work, and much much more! Read a free sample here.

Ask questions on my Discord server.

Sign up for my newsletter, where I summarize all my content month-by-month.

You can support my blog, my YouTube channel and my open-source projects by becoming a patron.

Have a nice day! /Karl Zylinski